Even With A Vaccine, The Economy Could Take Many Months To Return To Normal

Once we find a COVID-19 vaccine, our lives can return to normal, right? Economists don’t think so.

Even if the vast majority of the population become immune to the coronavirus tomorrow, leading economists think it could take six months or more before our economy is back to where it was before the pandemic hit. And if a smaller share of the population became immune, economists think returning to economic normalcy would likely take more than a year.

In this week’s edition of our regular survey of quantitative macroeconomic economists,8 conducted in partnership with the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, we asked the panel to close their eyes and imagine that a certain share of the population — 25 percent, 50 percent or 75 percent — were suddenly immune to COVID-19. Under each of those hypothetical scenarios, how long would it take to get back to pre-pandemic GDP (from the fourth quarter of 2019)?

As you can see, the varying levels of immunity made a big difference in the economists’ assessment of the speed of the recovery. The 32 economists who completed the survey collectively predicted that, if 25 percent of the population were suddenly immune to COVID-19, there would only be a 30 percent chance of GDP returning to its pre-pandemic level by the end of June 2021.

But for a universe where 75 percent of the population immediately had immunity to COVID-19, their forecast was much brighter: The economists thought, on average, that there was a 56 percent chance that GDP would be back to its pre-pandemic level by the middle of next year.

But even the consensus predictions for the rosiest scenario — which could, in reality, take months or years to emerge — weren’t actually that optimistic. In that fantasy world where 75 percent of Americans wake up tomorrow and are certifiably immune to the coronavirus, the economists thought there was only a 15 percent chance that GDP would return to its pre-pandemic level by the end of 2020, and only a 35 percent chance that GDP would hit that mark by the end of the first quarter of 2021.

A vaccine, in other words, is not an economic panacea.

“It’s important to keep in mind that although a pandemic was what started the whole recession, it’ll take some time to recover even when we get broad immunity,” said Tara Sinclair, an economist at George Washington University. “It’s not like people are just going to immediately go back to normal economic life.”

The problem, according to Sinclair and others, is that there’s been so much economic damage that a quick bounce-back is very unlikely, even after the threat of the virus starts to ebb. Millions of workers are unemployed, countless businesses are closed, and for many, the rhythms of work life may have been permanently changed. All of that helps explain why even under an unrealistically optimistic scenario, where much of the threat of COVID-19 vanishes overnight, a swift economic recovery might not immediately follow.

Not all of the economists in the survey were as pessimistic as Sinclair. If most Americans suddenly became immune to COVID-19, the virus could be contained relatively quickly, and most people would be eager to return to economic normalcy, according to Gloria Gonzalez-Rivera, an economics professor at the University of California-Riverside. She thinks consumers would be eager to take postponed vacations and head back to their favorite restaurants under this scenario, and decimated industries like hospitality and tourism would be able to revive quickly as a result. “We have a large pent-up demand, and the containment of the virus will be the catalyst for this demand to be released,” Gonzalez-Rivera said.

But Jonathan Wright, an economist at Johns Hopkins University who has been consulting with FiveThirtyEight on the design of the survey, told us that while some consumers might be eager to spend, it takes a long time for the economy to creak back into gear after recessions. “Individual people aren’t necessarily going to go on a spending spree whenever they stop being cooped up at home, and I certainly wouldn’t expect businesses to have that kind of impulse,” he said. “Business investment is generally muted after a recession, and I wouldn’t expect this one to be any exception.” That means, for example, it could take a while for unemployed workers to find new jobs, if the businesses that managed to weather the crisis are unwilling or unable to quickly scale up to where they were before the recession.

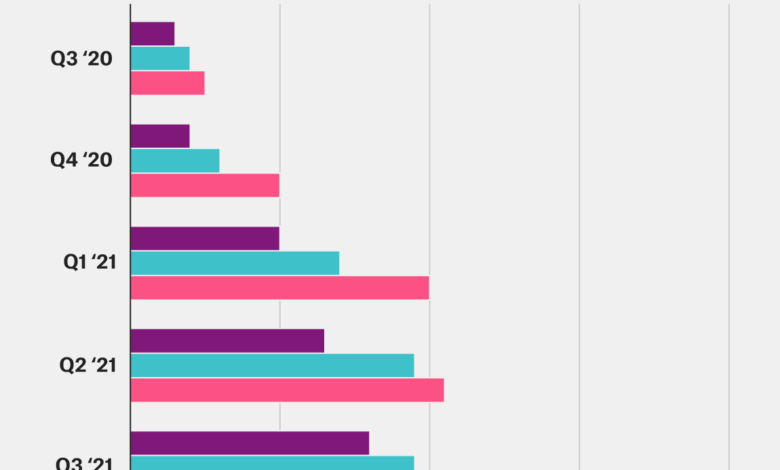

Optimism is growing for GDP recovery

It wasn’t all bad news, though. In a general sense, the economists have been slowly getting more optimistic about the economy over time. Since the last time we asked, on Aug. 10, their mean prediction for annualized third-quarter GDP growth has improved from +12.2 percent to +15.4 percent, with a sunnier best-case scenario and a less gloomy worst-case scenario. And their +5.8 percent forecast for fourth-quarter annualized GDP growth in this week’s survey is easily their highest prediction over the period in which we’ve asked the question (since June 8):

Allan Timmermann, an economist at the University of California, San Diego who has also been consulting with FiveThirtyEight on the survey, thought the uptick in the economists’ GDP predictions — although it was small — was noteworthy. To him, it signaled that either the economists think the worst of the crisis is over, or that they think the government will step in if the economy starts to slow down again.

In terms of jobs numbers, the economists also thought initial weekly unemployment-insurance claims were much more likely to dip below 700,000 for at least a week — in other words, returning to relatively normal numbers from pre-coronavirus times — between now and November than they were to return to a level above 1.5 million, where they had sat every week from March 21 through June 13.

How will weekly unemployment look late in the summer?

Probabilities that weekly initial unemployment insurance claims will fall into various ranges between now and the end of October, according to our survey of economists

| Weekly initial claims will be… | Probability |

|---|---|

| <700,000 for at least 1 week | 33% |

| Between 700,000 and 1.5 million each week | 50 |

| >1.5 million for at least 1 week | 18 |

That was the good news. However, the economists gave a 50 percent probability for claims hovering between 700,000 and 1.5 million every single week for the next couple of months — essentially leaving American job recovery in a sort of plateau: not as horrible as the job losses from early in the pandemic, but nowhere near a true recovery, either.

What might change economic expectations

We asked our survey group what might make their outlook by year’s end better — or worse — than the median forecasts they gave us in the survey. Most of the scenarios we offered surrounding the November election didn’t cause them to budge substantially from their existing projections. They were somewhat more likely to think that fourth-quarter GDP growth would be substantially lower if Trump won a second term and control of Congress remained unchanged than if Biden won the White House, or if Democrats won control of the Senate and the presidency. They also thought that an election result that’s viewed as illegitimate by a majority of the country would be likelier to drag down GDP.

What would make the economy look better (or worse)?

Average probabilities that certain scenarios would increase or decrease fourth-quarter GDP growth projections, according to economists

| In this scenario, Q4 GDP growth will be… | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | Substantially Lower | about the same | Substantially Higher |

| Vaccine approved by Election Day | <1% | 50% | 50% |

| K-12 schools stay open | 9 | 50 | 41 |

| Democrats control White House + Congress | 3 | 81 | 16 |

| Biden wins; Congress stays same | 3 | 91 | 6 |

| K-12 schools teach virtually | 19 | 81 | <1 |

| Trump wins; Congress stays same | 22 | 78 | <1 |

| Election viewed as illegitimate | 28 | 72 | <1 |

| No additional stimulus | 75 | 19 | 6 |

But the impact of the election was relatively small compared to other possible factors. On the downside, the economists still strongly believe that an ongoing lack of additional stimulus money from the federal government will cause serious damage to the economy. (You can read all about why in pretty much every previous installment of our survey.)

And on the upside, they believe that if K-12 schools reopened and maintained in-person learning through October, it would be a sign that the virus would likely be contained enough for other areas of the economy to improve as well. Meanwhile, if a COVID-19 vaccine were approved by the FDA by Election Day, they thought there was a 50 percent chance that GDP growth would be substantially better than their current forecast.

It might seem surprising to political junkies that something as momentous as the presidential election would have a much smaller predicted effect on the economy than schools reopening or Congress passing additional stimulus. Part of the issue, Sinclair said, is that if the election has an impact on the economy, it probably won’t be immediate. But she said that in general, there may not be much the next president can do to alter the country’s economic course, particularly if the House and Senate remain divided.

“Economists don’t think about the president as having a lot of power directly over economic growth,” she said. It’s Congress, after all, that gets to decide how the country’s money is spent. And while that might be somewhat different in a recession caused by a pandemic, it’s harder to predict which presidency would produce better growth numbers. “The way that the economy will look under these two different candidates is different — no question,” she said. “But quantitatively, will one clearly produce better GDP numbers than the other? I’m not sure.”

Some of these scenarios offer a glimpse into what a better-than-expected late summer and early fall might look like. But it’s also telling that the economists only gave a 50 percent chance of the economy being substantially improved with a vaccine quickly getting approval. That was in keeping with our earlier findings about the relationship between immunity and economic recovery: Yes, it’s better to have an effective vaccine earlier. But it will still take a long time to undo the damage of this recession, even after the root cause — the virus itself — recedes.