New GAO Report Details Sugar Program Dysfunction

For decades the federal government has been manipulating the domestic sugar market through a system of import and production restrictions that increases the price of sugar. This program is great for sugar producers, but—as a report released last week by the Government Accountability Office makes clear—it hurts pretty much everyone else. Once the sugar program’s costs are subtracted from its benefits, the report notes that various studies suggest a net loss to the economy ranging from $780 million to $1.6 billion per year.

That by itself makes the sugar program richly deserving of termination. However, additional details in the GAO report reveal a scale of dysfunction that should place the program firmly in Congress’s crosshairs. The following are six key points raised in the report:

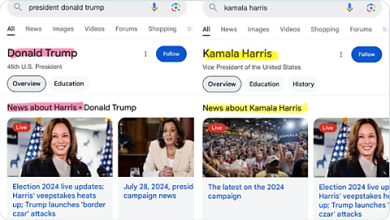

The program significantly raises the cost of sugar in the United States.

As can be seen from the GAO chart, the price of raw sugar in the United States is significantly higher than abroad. In recent years it has been twice as expensive as raw sugar in other countries.

US sugar producers receive substantially more government support than their foreign counterparts.

Although the US sugar industry alleges “massive subsidization” by leading sugar‐producing countries such as Brazil and India and claims to be merely trying to “survive in a world of heavily subsidized sugar,” the GAO report makes clear that the United States is among the most egregious practitioners of such subsidies. Indeed, the report shows that the United States is surpassed only by China in its enthusiasm for sugar subsidies as measured by the industry’s percent of revenue from government support.

The GAO report also points out that, beyond government measures explicitly devoted to supporting the US sugar industry, the business further shields itself from foreign competition via the use of antidumping and countervailing duty laws. As the report states:

Both the U.S. sugar program and the U.S. antidumping and countervailing duty suspension agreements protect the domestic sugar industry. This makes sugar an outlier in terms of trade protection; even before accounting for the suspension agreements with Mexico, sugar had by far the highest trade protection of any U.S. good, agricultural or nonagricultural, according to a 2017 USITC study.

The sugar program boosts the profits of sugar farms. Using both a previous GAO study and other studies, as well as data from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), the report calculates that the US sugar program benefits each sugar farm by approximately $100,000 to $190,000 per year (although it cautions that the amount will “vary substantially” by farm size). These sugar farms, the report adds, are “substantially more profitable than non‐sugar farms” to the tune of 24.3 percent higher net income per acre for farms growing sugarcane (compared to the average non‐sugar farm) and 54.2 percent higher net income per acre for the average farm growing sugar beets.

Given the higher acreage of sugar farms compared to non‐sugar farms, this means the overall net income of farms growing sugar beets was over seven times higher than non‐sugar farms while farms growing sugarcane saw profits over eight times higher.

Furthermore, this is based on data from 2017. But from 2017 to 2022, the report adds that sugarcane prices rose by 44 percent and sugar beet prices rose by 48 percent while total US farm production expenses rose by 26 percent. In other words, the profitability of sugar farms may have further increased.

The poor disproportionately bear the burden of paying for the sugar program. The GAO report points out that the country’s lowest‐income households spent an average of 30.6 percent of their income on food in 2021 compared to 7.6 percent for the highest‐income households. Therefore, policies such as the sugar program that raise the cost of food—and there are plenty of foods that use sugar as an ingredient—are disproportionately felt by the poorest Americans.

The sugar program undermines US food manufacturers. Unsurprisingly, the GAO found that costly sugar is harmful to food manufacturers who rely on sugar as an input for the products they make. While sugar is a small cost for many food producers, it averages as much as 9 to 10 percent of material costs for the makers of candy and chocolate and, as the GAO notes, likely also harms other industries where sugar is an important ingredient, such as cookies and breakfast cereals (among others).

But the harm goes beyond just higher costs. Due to US restrictions on sugar supply, simply getting access to adequate amounts of sugar can be another issue for food manufacturers. That’s no small thing. According to representatives of sugar‐using industries contacted by the GAO, sugar supply issues have, at times, “forced some confectioners to temporarily shut down production, cancel orders, or pay double the typical price of sugar.”

This helps explain why some food manufacturers have shifted production to other countries where they can be assured a ready supply of sugar at competitive prices. That means fewer jobs in the United States. A 2015 study highlighted by the GAO found that the US sugar program depressed employment in food manufacturing by 18,500 workers.

The sugar program’s tariff rate quote is inefficient. To help keep supplies low and prices high, the United States employs a tariff‐rate quota that allows limited amounts of raw and refined sugar to enter the country each year under a relatively low tariff and forces all other imports to pay a tariff that is significantly higher. While the tariff‐rate quota for refined sugar sets aside certain amounts for imports from Canada and Mexico and administers the remainder on a first‐come, first‐served approach to imports from all other countries, raw sugar imports use a more complex system that divides the tariff rate quota among 40 countries.

One big problem identified by the GAO report is that many of these quota assignments go unused. Of the forty countries receiving tariff‐rate quotas, two have never used their quota, seven have not done so in the last fifteen years, and twenty have filled less than 75 percent of their allocations in total between 2006 and 2022.

While the USDA has the power—which it often exercises—to both reallocate and increase the tariff‐rate quota during the year, significant problems still present themselves. As the GAO report states:

However, in 5 of the 11 years for which reallocations occurred between 2010 and 2022, the reallocations were announced in June or later. According to some tariff‐rate quota‐holding countries, this timing—three-quarters of the way through the quota year—occurs after they have already shipped their base allocation. Furthermore, these countries stated the timing makes it difficult to impossible to arrange the additional shipment on short notice.

Additionally, some sugar users we spoke to told us the timing of the reallocation and increase process has caused supply chain issues and has prevented sugar users from obtaining sugar needed for production. Specifically, they mentioned that when raw sugar is imported late in the fiscal year, sugar refineries are typically operating at or close to full capacity. As a result, the reallocated and increased raw sugar can take months to be refined for production, limiting the amount of sugar available, according to sugar users.

Every year dating back to 1996, raw sugar imports have been less than the in‐quota quantities established by USDA, leading to persistent shortfalls.

From 2006 through 2022, the report points out that the United States imported an average of 13 percent less raw sugar than the in‐quota quantities that had been set during those years. That percentage, the GAO adds, works out to about 2.8 million metric tons over that period with an estimated value of $1.67 billion. That’s money that was effectively left on the table due to the tariff‐rate quota’s inefficient nature.

Summing up

Cato scholars have been pointing out the costly and nonsensical nature of the US sugar program for years. This latest GAO report only further underscores what has long been known. With the 2018 farm bill set to expire this year, the time is ripe for Congress to take a fresh look at US agricultural policy. Repealing this sugar industry giveaway should be high on any list of potential reforms.