Democrats Helped Build The Social Safety Net. Why Are Many Now Against Expanding It?

Today’s Democrats fancy themselves as the party that trusts the evidence — wherever it might lead. This is why they invest heavily in science and technology and set up arms of government to translate that knowledge into action. But despite claiming to prioritize new ways of improving our society, Democrats don’t always act in ways that are rooted in research.

In fact, sometimes they actively resist doing what the evidence says — especially when it comes to implementing policies that give financial benefits to people low on America’s societal totem pole. It’s not always said out loud, but the reality is that some Democrats, and American voters in general, do not think very highly of poor people or people of color — there are countless examples of how society is quick to dehumanize them and how politicians struggle to address their needs in a meaningful way. These patterns of thinking and misleading portrayals of marginalized people too often mean that the policies that could help them most are opposed time and time again.

That opposition is, of course, rarely framed in terms of antipathy or animus toward a particular group. Instead, it is often framed as “rationality,” like adherence to “fiscal conservatism,” especially among members of the GOP, who have long abided by small-government views. But some Democrats are really no different. Consider President Biden’s reluctance to cancel student loan debt, or the federal government’s hesitancy to provide free community college, or West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin’s recent opposition to including the child tax credit in the Build Back Better plan, reportedly on the grounds that low-income people would use the money on drugs. Indeed, politicians across the political spectrum have found a number of scapegoats to use while arguing against expanding the social safety net, including playing to Americans’ fears about rising inflation rates. As a result, various programs that would help people — namely the poor and people of color — have become taboo.

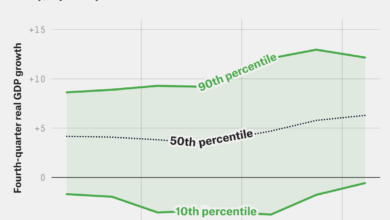

What’s striking, though, is that if you actually look at most social science research, investing in the social safety net is fiscally responsible — it pays large dividends for both individuals and our collective society. Economists have studied this for decades, finding that anti-poverty and cash-assistance programs executed both in and outside of the U.S. are linked to increased labor participation in the workforce, while investing in childcare benefits not only children, but the broader economy and society they are raised in. Moreover, newer initiatives like canceling student debt could add up to 1.5 million jobs and lift over 5 million Americans out of poverty in addition to freeing many Americans of the debt trap that is contributing to a lagging housing market and widening racial wealth gap. Other research suggests that those saddled with student loan debt would be more likely to get married or have children if their dues were forgiven.

That is the evidence. Yet, rather than acting on it, there has been a tendency to highlight stories and tropes about people who might waste the resources invested in them. And that’s oftentimes enough to undermine public and political support for these policies. So what we’re seeing from some “moderate” Democrats today is likely born out of an inherent distrust of what might happen if you just give people money or help them through an expanded social safety net.

But if we look in the not-too-distant past — less than a hundred years ago, in fact — we quickly see that Democrats didn’t always oppose distributing money to support Americans’ well-being. In fact, former Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt rolled out safety-net programs like Oprah would give away her favorite things. In response to the Great Depression, Roosevelt oversaw a massive expansion of the social safety net during the 1930s and ’40s, which included giving grants to states that implemented unemployment compensation, aid to dependent children and funding to business and agriculture communities. Recognizing the importance of a safety net to protect people from “the uncertainties brought on by unemployment, illness, disability, death and old age,” the federal government also created Social Security, which it deemed vital at the time for economic security. And in the 1960s, long after the Great Depression was over, the government created the Medicare program for similar reasons under former President Lyndon B. Johnson, another Democrat.

What is clear from these examples is that the federal government once understood the importance of a robust safety net for the health, well-being and the broader functioning of our society. The caveat, however, is that this general understanding does not extend to our thinking about all Americans; the government was supportive of these policies when most beneficiaries were white. But when people of color started actively utilizing and benefitting from these same programs, they became harder to attain and, in some cases, overtly racialized.

That was particularly true in the 1970s and ’80s when conservative and right-wing political candidates vilified Americans on welfare. During his initial presidential run, Ronald Reagan would tell stories and give numerous stump speeches centered on Linda Taylor, a Black Chicago-area welfare recipient, dubbed a “welfare queen.” To gin up anti-government and anti-poor resentment among his base, the then-future Republican president villainized Taylor, repeating claims that she had used “80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans’ benefits for four nonexistent deceased veteran husbands, as well as welfare” as a way to signal that certain Americans — namely those of color — were gaming the system in order to attain certain benefits from the federal government. Reagan wasn’t alone, however. In fact, his tough stance on alleged welfare fraud and government spending on social programs encapsulated the conservative critique of big-government liberalism at the time.

Democrats, however, weren’t that different either. Former Democratic President Bill Clinton’s promise to “end welfare as we know it” in the 1990s included stipulations like requiring a certain percentage of welfare recipients to be working or participate in job training. This helped foster, in turn, a belief that there were people who played by the rules and those who didn’t (namely Black Americans). And once politicians started worrying about (Black) people taking advantage of the system, the requirements needed to acquire certain societal and financial benefits became even harder to obtain.

But all of this implicit rhetoric about reducing government waste by cracking down on marginalized people does not hold up to scrutiny when examining the evidence. The reality is that fraud among social safety net beneficiaries is extremely rare, and much less costly to society than, say, tax evasion among the richest 1 percent. Yet we spend an incredible amount of money trying to catch and penalize the poor instead of helping them.

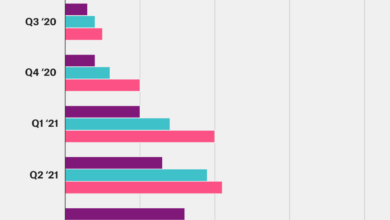

Moreover, polls show that Americans — particularly Democrats — overwhelmingly want to expand the social safety net. According to a 2019 survey from the Pew Research Center, a majority of Democrats and Democratic-leaners (59 percent) and 17 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaners said that the government should provide more assistance to people in need. Even this October, around the time when Democrats were negotiating the size of the omnibus Build Back Better Act, a CNN/SSRS poll found that 75 percent of the party’s voters (and 6 percent of Republicans) preferred that Congress pass a bill that expanded the social safety net and enacted climate-change policies.

However, despite many Americans wanting an expansion of the social safety net, it is still often hard to sell voters on these programs — especially if they’re wrapped up in large policy packages (i.e. Obamacare) or associated with someone voters dislike (i.e. former Democratic President Barack Obama). Consider that a Politico/Morning Consult survey from late last year found that only 39 percent of Americans who received the child tax credit said it had a “major impact” on their lives. Moreover, only 38 percent of respondents credited Biden for the implementation of the program.

The fact that many expansions of the social safety net aren’t initially popular makes it all the easier for Democrats to fall back on the stories people tell themselves about different groups of people and whether they deserve help. And sometimes, those portrayals affect the concerns we have about members of those groups and the explanations we generate for why they experience the outcomes they do in life. As earlier expansions of the social safety net show, the U.S. hasn’t always been allergic to giving people money, but there now seems to be this unspoken idea that poor people and people of color can’t be trusted to spend “free” money or government assistance well.

This thinking, though, poses a problem for Democrats because, for years, they’ve branded themselves as the party that promotes general welfare by advancing racial, economic and social justice. At the same time, they continue to fall short on campaign promises to expand the social safety net despite many poor people, and people of color, having fought long and hard to put them in office. The fact that so many of today’s Democrats are still prisoners to antiquated tropes about who gets — or is deserving of — government benefits is a dangerous one, because it causes people to push members of those groups outside of their “moral circles” — the circle of people that they think they have a moral obligation to help.

Of course, breaking this chain of thought won’t be easy because it would require Democrats to break the long-standing mindset that poor people are in their current situation because of a series of “unfortunate” choices. It would also probably require them to stop worrying about how Republicans might falsely reframe social safety net programs as dangerous, especially given ongoing concerns regarding inflation and the economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. But at the end of the day, that shouldn’t matter: While the politics might not be immediately convenient and the effects of these programs not immediately seen, that is not necessarily a reason to defer implementing them. Focusing solely on the short-term effects is not only short-sighted, but dangerous. And Democrats stand to lose more than the support of their base if they refuse to act.