The symptoms of this particular form of delayed recovery from Covid-19 are a strange mix. They include lethargy, sluggishness, depression, and inability to focus. It is a bit like long covid, except that the victim here is not a person, but India’s economy.

The pandemic continues to affect lives, livelihoods, and the economy, wreaking havoc from a recent second wave and the threat of a third wave already on the horizon. The precarious state of affairs has led to reduced consumer and business confidence. With the real death toll of the virus around ten times more than official figures (according to the Centre for Global Development, Washington D.C.), it is no surprise that the country is finding it difficult to get back on its feet.

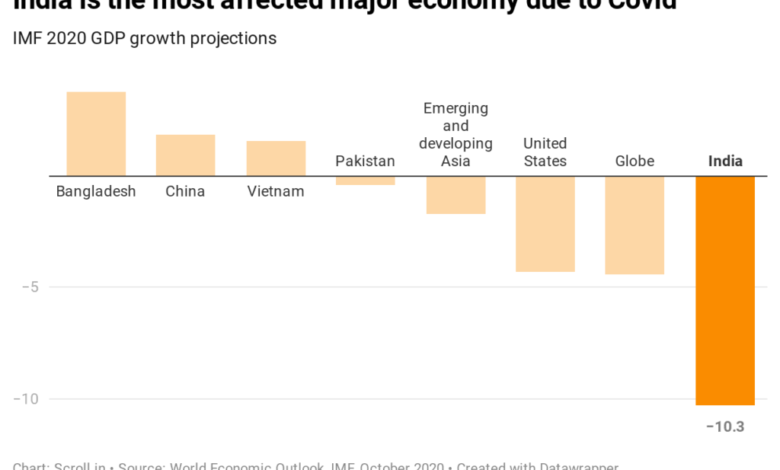

India also stands apart because its economy has been affected severely. As richer nations begin to recover, India is stuck with limp demand, persistent unemployment, falling savings and investments, and high inflation. Most of these problems predate the pandemic but were worsened by it. The Indian economy was mainly running on consumption, which has been hit badly by the two waves of infections. According to official data compiled by the National Statistical Office, the nation witnessed a contraction of 7.3%, the worst on record and more than any other major Asian economy.

Although the recent quarter witnessed a 20.1%, this has been largely attributed to a low base effect, rather than major improvement in other high-frequency indicators.

Source – IMF

A survey of white-collar workers by Grant Thornton (a consulting firm) found that 40% of employees had suffered a pay cut last year. Another survey, of 3000 informal workers in Delhi, concluded that male breadwinners had on average face a 39% fall in income in the past year. Most economists predict a reasonably robust growth this year, enough to compensate for last year’s debacle.

However, when we talk about the medium term, it’s not about how fast “normal” growth will resume, but about how many years have been lost, thus possibly even redefining the new normal. The new normal might be characterized by the 7-8% growth that India achieved in the 2000s or the 3-5% growth of the distant past. A recent study by NCAER suggests that without a fast-growth strategy, India may never be able to compensate for the lost growth and capitalize on the demographic dividend of a relatively large workforce with fewer dependents.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Acknowledging the pressure, the government announced a further $85 billion in stimulus measures (about 3% of GDP), in addition to a nominal $300 billion pledged last year. It has extended the supply of free food grains that has helped many families stay afloat and sustain themselves. It has also shored up banks and helped small businesses, especially in severely hit sectors like tourism. In real terms, however, government expenditure is not expanding but shrinking. In the quarter ending in June 2021, government investment in new projects fell by 42% relative to the previous quarter. According to NCAER, total expenditure this fiscal will amount to 16.3% GDP, which is a significant decrease from the previous year’s 17.8%.

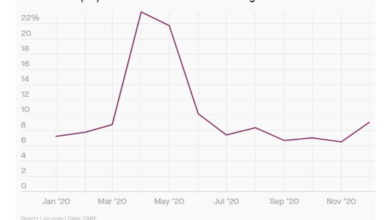

Source – The Hindu

Another concern is the adverse impact of the pandemic on the already stressed banking sector, which is inherently saddled with NPAs (Non-Performing Assets). Fears concerning a resurgence in bankruptcies that may affect the NBFC sector and microfinance institutions in addition to commercial banks are rising.

Rising inflation could also pose a serious risk due to supply dislocations and rising commodity prices. Higher prices erode the purchasing power of consumers and are likely to increase production costs. Risks of inflation can weigh on pent up demand and dent demand recovery. The money-printing spree by the United States is also behind some of the inflation that’s being seen around the world and has ripple effects on our country. Experts are of the view that price pressures should be tackled sooner rather than later.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

The government does keep a wary eye on its credit rating, inflation, and interest rates. But if India’s post-covid troubles are due to anything, they can be blamed on a legacy of poor choices by its leaders, with shying away from a fuller transition to a truly competitive economy and a chronic failure to invest in human capital. With the risk of a potential third wave looming large, we are walking on thin ice right now.

Source – India Today

Although the IMF and a few credit rating agencies are hopeful of a significant recovery next fiscal, it is largely contingent on government action and the prevailing Covid-19 situation. Both the RBI and the government must be proactive and prepared to prop up the economy as well as possible in the medium term. The country must be fully equipped to face the imminent threat of subsequent waves of infection.

If you construct a house poorly and a storm hits, leaving you completely drenched, the storm can’t be the only one to blame, can it? Unfortunately, we might experience more storms in the foreseeable future.

Writer- Kanishq Chhabra

Editor- Sohini Roy

The post The Elusive Growth appeared first on The Economic Transcript.