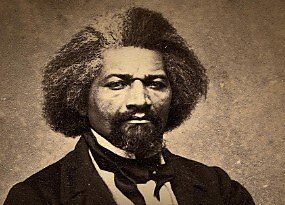

Frederick Douglass: Self-Made Man

It was on this day, 130 years ago, that the abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass—died at his home near Washington, DC, at the age of 77, shortly after speaking at a woman’s suffrage meeting. It was characteristic of the “Sage of Anacostia” that he had carried on with his mission up to the literal end of his life. Only a little while earlier, or so the legend goes, a young man had asked his advice about what to do with his life. “Agitate,” replied Douglass. “Agitate, agitate.”

Douglass was born into slavery on a Maryland plantation and after enduring bondage in both the city and the country, he managed to escape on the underground railroad, first to New York and then to Massachusetts. He found it hard at first to adjust to life as a free man. “I was indeed free—from slavery, but free from food and shelter as well,” he recalled in his memoirs. But in the north, he could work and provide for himself, and that sense of self‐responsibility and economic liberty was a thrilling deliverance. “Slavery had inured me to hardships that made ordinary trouble sit lightly upon me…. The consciousness that I was free—no longer a slave—kept me cheerful.”

Devoted to self‐improvement, he devoured books and newspapers, particularly the abolitionist paper The Liberator, which he would tack on the wall of the blacksmith shop where he operated the bellows, so he could read while working. Shortly afterward, he joined Liberator editor William Lloyd Garrison as a speaker for the abolitionist movement. But he was eventually to break with Garrison over the latter’s belief that the Constitution protected slavery, and was, therefore, a “pact with hell,” which abolitionists should shun.

Garrison thought that participating in politics under the Constitution—running for office, filing lawsuits, or even voting—lent moral credibility to the evil of a regime that he believed was rooted in slavery. The founding fathers, after all, were either slave owners themselves or had agreed to preserve slavery in a devilish compromise. Rather than seeking to reform the system from within, therefore, abolitionists should set themselves against the constitutional order, under the motto Garrison printed atop every issue of The Liberator: “No union with slaveholders.”

Although Douglass initially agreed with Garrison, denouncing the Constitution in the eloquent language that would earn him worldwide fame as an orator and author, he changed his mind in the 1840s, after spending a year in Great Britain among English abolitionists who had accomplished a great deal by participating in the political system. Douglass came to see that refusing to participate in politics really meant prioritizing one’s own sense of moral sanctity over the actual work of helping the enslaved. And upon his return to the United States, he began reading the writings of legal scholars such as Gerrit Smith, Lysander Spooner, and Joel Tiffany, who argued that the Constitution did not, in fact, protect slavery. On the contrary, they argued, it never even mentioned slavery—and far from providing it with legal guarantees, the Constitution empowered Congress to restrict, and even abolish it, if only federal officials had the will.

Thus in 1851, Douglass announced his break with the Garrisonian anarchists. The Constitution, he was now persuaded, was, in both principle and practice, an anti‐slavery document. His argument began with two rules of interpretation. First, only the Constitution’s actual words count as law—not the desires or intentions of those who wrote it. Second—following a rule set down by the Supreme Court some years before—the Constitution should be interpreted in favor of freedom whenever possible. With these principles in mind, the Constitution’s allegedly pro‐slavery features turned out not to secure slavery at all: the 3/5ths clause, for example, not only didn’t protect slavery, but actually would reward any state that abolished it. The so‐called “fugitive slave clause,” which does not actually mention slaves, could be interpreted as applying to runaway apprentices, instead. In short, Douglass thought that interpreting the Constitution as pro‐slavery was like trying to prove you owned property by pointing to a deed that made no mention of the property.

Moreover, other provisions of the Constitution were incompatible with slavery. The Fifth Amendment forbade depriving people of liberty without due process of law. The Privileges and Immunities Clause barred the state from depriving American citizens of basic liberties. As for “We the People,” did that not include black Americans? They were just as entitled to citizenship as whites, Douglass argued—and the Constitution made no mention of “white” versus “black” people. When, in 1861, southern states felt compelled to abandon the Constitution to protect slavery—by declaring themselves no longer part of the United States—Douglass saw this as proof he’d been right: the Confederacy could point to nothing in the Constitution that protected slavery.

In recent years, it has again become fashionable to argue that the Constitution was written to preserve slavery indefinitely, by white slaveowners who did not believe black people were equally human, or that they could attain or deserve the status of citizenship. Douglass would have instantly recognized that these arguments as those of both pre‐Civil War advocates of slavery, and of Garrison and his allies.

“It may be said that it is quite true that the Constitution was designed to secure the blessings of liberty and justice to the people who made it,” he said in an 1860 speech, “but was never designed to do any such thing for the colored people of African descent. This is Judge Taney’s argument [in the Dred Scott case], and it is Mr. Garrison’s argument, but it is not the argument of the Constitution.” Worse yet, Douglass observed, there were even black Americans who endorsed the Dred Scott theory that the Constitution was a white‐supremacist document. The “worst thing” about that notion, he said, was that it “forces upon [the black man] the idea that he is forever doomed to be a stranger and a sojourner in the land of his birth, and that he has no permanent abiding place here.” The truth was—and is—that the Constitution is as much a guarantee of the rights of blacks as of whites.

But Douglass was not merely a defender of the rights of black Americans like himself. He insisted on the rights of women, as well. He attended the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, and in 1886 even spoke out in favor of women serving in the military. Still, when the Fifteenth Amendment was proposed—which guaranteed black men the right to vote, but implicitly allowed states to forbid women from voting—Douglass supported it, despite the furious condemnation of many female allies.

It was crucial, he insisted, for black men to get voting rights as quickly as possible, to defend themselves from racist white majorities. Once that was secure, he pledged that he would devote his efforts to supporting woman suffrage. And he proved as good as his word.

Frederick Douglass devoted his entire life to one central principle: the principle of equal liberty enunciated in the Declaration of Independence and protected by the Constitution. All people, everywhere, he believed, have the right to liberty, and should use whatever tools are at their disposal to secure that freedom both for themselves and for their fellow citizens.

Americans are fortunate enough to have an invaluable tool at their disposal: the Constitution of the United States, if only they will have the courage to respect and enforce it. We are, moreover, fortunate enough to have an example in a man who devoted his life’s energies to vindicating that principle for all.

Timothy Sandefur is vice president for legal affairs at the Goldwater Institute, where he holds the Clarence J. & Katherine P. Duncan Chair in Constitutional Government. He is the author of eight books, including Frederick Douglass: Self‐Made Man (Cato Institute).