As she sat in the sun in her Ford Fiesta inching her way through a long line of cars to get fuel, Maria Mussolini tried to while away the time by browsing her phone. After four hours, she still hadn’t reached the station and was drenched in sweat due to the heat. She needed to go to the loo but feared she might lose her place in line if she went searching for one. As she refuelled her car, she started to look for a pharmacy that still had a sufficient stock of medicines. On the way, she passed many traffic lights that didn’t work and supermarkets with empty shelves. A desolate ambience engulfed the streets, which were covered with fallen leaves and garbage.

She could see a person graffitiing the walls of various shops in the market with slogans of protest against the ruling government. She couldn’t find the medication she required and returned home empty-handed. “I’m dejected, exasperated and infuriated,” she said, summarizing the feelings of numerous Lebanese about the economic crisis that has transformed routine tasks into nightmares that occupy their days and empty their wallets.

Lebanon has been mired in a catastrophic socio-economic and political crisis for almost 2 years. Let us take a walk down the road to understand how the economy went into a tailspin.

Lebanon was already grappling with high levels of debt following the civil war of 1975-1989 as a result of financial mismanagement and corruption by the successive governments and sectarian elites. By the time the crisis erupted in October 2019, the nation was reeling under four major challenges: its public sector debt had reached such high levels (150% of national output, 3rd largest in the world) that economists were confident of an impending default. Secondly, its banking sector, having lent three-quarters of deposits to the government, had essentially become highly illiquid and bankrupt. Third, there had been virtually no economic growth for an entire decade- a situation with acute socio-political ramifications.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the country lacked political leadership. The Hariri government in 2019 was unable to reach consensus to introduce economic reforms, which was a precondition for foreign aid.

Source – Reuters

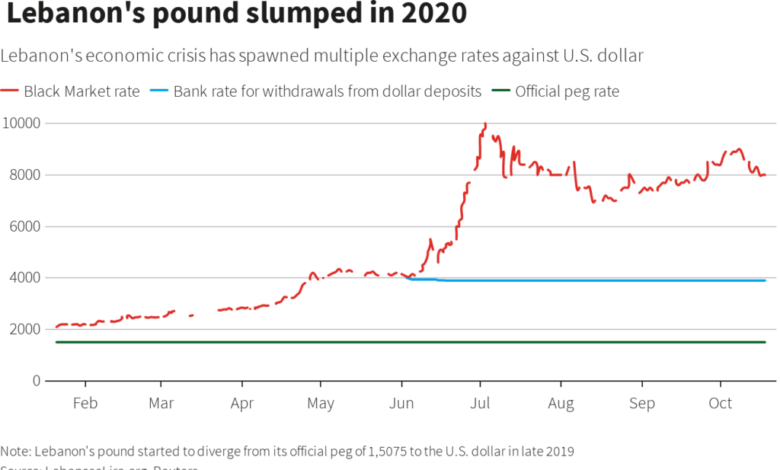

These conditions manifested an uprising from the Lebanese, who sensed a looming economic downturn and were frustrated by the utter lack of action by the political class. At the beginning of October 2019, a shortage of foreign currency led to the Lebanese Pound losing its value against the U.S. Dollar on a newly emerged black market for the first time in two decades (contrary to the official peg of 1,507.5 to the Dollar). And when importers of wheat and fuel wanted to be paid in dollars, unions called for strikes.

Additionally, the unforeseen wildfires in the country’s western mountains highlighted an underequipped and underfunded fire service. Moreover, people were getting increasingly frustrated by the government’s failure to provide basic services like public healthcare, safe drinking water and regular electricity. In mid-October, the government proposed a slew of new taxes on tobacco, petrol and even voice calls via messaging services like WhatsApp to collect more revenue, but a backlash forced it to drop the plans.

However, this rout unleashed a wave of discontent that had been simmering in Lebanon for years. Thousands of Lebanese took to the streets, leading to the resignation of the Hariri government. Newly appointed Prime Minister Hassan Diab eventually announced that the country would, for the first time in history, default on its foreign debt.

Source – Haaretz

Predictably, capital inflows came to an instant halt, and banks which were already insolvent faced a liquidity crunch. A sharply depreciating Lebanese pound resulted in hyperinflation (averaging 84.3% in 2020), eroding people’s real wages and purchasing power. Moreover, to add to the woes of the ailing nation, the Covid-19 crisis shook the country’s social security net, sending more than half of its population below poverty line. A devastating explosion on 4th August 2020 in downtown Beirut further fueled the growing dissent, with more than two hundred people killed and 300,000 people left homeless.

The convergence of these large negative shocks led to the breakdown of the economy: According to the estimates by the World Bank, real GDP contracted by 20.3% in 2020, on the back of a 6.7% contraction in 2019, plummeting from $55 billion in 2018 to $33 billion in 2020, while GDP per capita fell by 40% in dollar terms. Such a harsh contraction is usually correlated with conflicts or wars. Subject to exceptionally high unpredictability, real GDP is projected to contract by a further 9.5% in 2021.

A major contributor to this economic doom has been the nationally regulated Ponzi scheme by the government and the central bank. The purpose of pegging the Lebanese Pound to the U.S. Dollar was to restore confidence after a 15-year civil war. But it was premised upon an unproductive economy and an intricate labyrinth of transactions that came to correspond to a Ponzi scheme. Most Arab countries with fixed currencies defend their pegs with revenue from oil and gas exports, and Lebanon has none.

It has few goods exports at all: at their peak in 2012 they reached $4.4 billion, against $21.1 billion in imports. Other sources of income, such as property and tourism, were insufficient to justify and sustain a peg, with fiscal deficits exceeding 10% of GDP and current account deficits over 25%. It did, however, have one dependable source of dollars, a booming financial sector that, during its prime in 2018, held 269 trillion pounds of deposits, then worth $179 billion-more than three times the country’s GDP.

To funnel some of the dollar deposits (which accounted for two-thirds of total deposits) into its coffers, the central bank-Banque du Liban crafted a scheme called “financial engineering”, popularly referred to as “the swap”. From 2016, it started to exchange local-currency debt with the finance ministry for dollar-denominated bonds, which were subsequently sold to commercial banks at high rates of return. Banks also had the option to borrow pounds against their dollar deposits at the central bank, and then lend them back to it, with a spread of 11 percentage points on the transaction.

Source – The Arab News

Calling this scheme a short term fix, Riad Salame, the central bank governor, emphasized that the Banque du Liban was not responsible for Lebanon’s deficits, and passed the blame on politicians. But the central bank was responsible for making those debts possible and tying everyone in a quagmire of mutual liabilities. By 2018, the central bank was financing a large portion of the fiscal deficit, and by 2019 most of Lebanon’s public debt was owned by banks and the Banque du Liban.

The International Monetary Fund, in its annual assessment of the Lebanese economy, reckoned that banks’ combined exposure to the government and the Banque du Liban amounted to 69% of their total assets in May 2019, chiefly because of the rise in their deposits with the central bank.

Sustaining this fragile arrangement required an ever-larger supply of fresh dollars, which necessitated higher yields to lure depositors. The average interest rates on dollar deposits increased from around 3% in 2016 to almost 7% within a span of three years. But after a decade of sluggish growth, bank deposits flattened off in late 2018 and have been falling ever since, with banks severely curtailing dollar withdrawals. In March 2020, Lebanon defaulted when it failed to make a payment of $1.2 billion against a bond. The estimated cumulative loss incurred by the banking sector was $83 billion.

Hassan Diab proposed major financial reforms to the banking system, in order to fulfil the conditions for a financial agreement with the IMF worth $10 billion. But most of his plans, including auditing the central bank, were obstructed by lobbying banks and political interests.

On 6th July, 2021, Mr. Diab, who’s now assumed a caretaker role as acting Prime Minister, said that the country is days away from a social explosion. For nearly a year, the country’s politicians, divided by sect and inherently corrupt, have failed miserably to form a new government and undertake reforms called for by foreign leaders. A recently passed plan to replace subsidies with a $556 million cash-aid programme for the poor has been met with funding hurdles. Political hubris by Lebanon is preventing the World Bank’s $246 million loan to expand the social safety-net, leading to falling patience from the latter with each passing day.

Many others like Maria are suffering from the debilitating situation that is prevalent in the country. Poverty is rising, businesses are closing and basic services are failing, with no light visible at the end of the tunnel. A radical and herculean effort is required from all stakeholders to improve the decimated state of Lebanon.

Written by- Kanishq Chhabra

Edited by- Radhika Khandelwal

The post A Myriad of Crises appeared first on The Economic Transcript.